Artificial intelligence (AI) programmes and data analysis technology are poised to replace more traditional methods of geology and mineral exploration. World Mining Frontiers writer Greg Noone talks to Sam Cantor, head of economic geology at Minerva Intelligence, and Shawn Hood, chief technological officer at GoldSpot, to find out more.

The image of mineral exploration in the public imagination is perhaps the aspect of mining that remains most disconnected from reality. The figure of the prospector is one flung out of time from the Gold Rushes of the 19th century, a flinty-eyed coot adept at navigating wilderness at the edge of the known world, his worldly goods sitting precariously on the back of a tired and surly mule.

Most often bit players in a grander narrative of the frontier, these men find their gold by panning for it in rivers, their efforts informed by subtle clues in the positioning of mountains or the strata of ancient rock.

Popular culture has done little to update this image for the present day. It is possible, of course, that one will find gold by panning for it, but nowadays you’ll have more luck if you train for several years as a geologist before joining a dedicated exploration team.

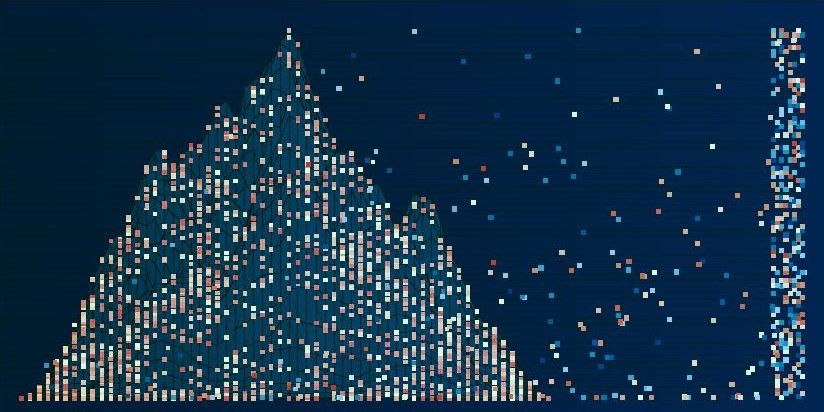

Their work is decidedly more complicated, informed by the huge reams of data on as many aspects of the surrounding landscape as they’re capable of measuring, from read-outs on local rock and soil compositions, to aerial and satellite photos, seismic disturbances, radioactivity, magnetic permeability and the distribution of certain microorganisms, gases and animal species.

All of these individual assessments of the various aspects of the landscape are gathered and, like so many pieces in a jigsaw, fitted together to create a picture of where a mineral or metal is likely to be found in the target area.

And just like solving a puzzle, this process can prove laborious, reliant on individual assumptions that, if not questioned appropriately at the outset, can skew the result of the model and lead to a futile round of drilling assessments.

That problem can be insurmountable in certain locations, explains Minerva Intelligence’s head of geology, Sam Cantor.

“You’ve got world-class gold deposits in China and Tibet and all these other places where, on a metre-to-metre level, the variability of the gold veins is constantly tripping up the geologists, because they’re so unpredictable on the scale of a person,” says Cantor.

So much data ends up being collected on occasions like these that doesn’t end up being used – data that could provide vital clues as to where mineral deposits are actually located.

It is for this reason that Cantor and others believe mineral exploration is crying out for an intervention from AI technology. Minerva Intelligence is one of a host of new start-ups using AI to assume much of the burden of quantifying the immense amounts of data acquired in the modern prospecting process, known within the industry as “target generation”.

In doing so, not only could hundreds of geologists be released from the drudgery of data curation, but the increased processing power of AI relative to a humble rock expert could divine new insights on claim areas that were hitherto impossible a decade ago.

Different approaches to AI technology in mineral exploration

On paper, target generation is similar to the kinds of processes that machine-learning algorithms and neural networks have proved so successful at rationalising in the past: a repeatable task that may prove onerous to a human, but one with enough variability that it cannot easily be automated by lines of pre-written computer code.

The problem is that mineral exploration does not afford the many thousands of clean examples of such a task that an AI can count on when being trained to recognise sounds or objects, which has made it extremely laborious to craft a machine intelligence technology capable of being adapted to many different landscape scenarios.

“Every single person in the AI space will tell you that cleaning the data is generally the hardest part,” explains Cantor. “All of those rock names are jumbled throughout the different generations, and people haven’t been standardising. Nobody’s reviewed it and gone back and corrected it.”

Only when all the data sets are speaking the same geological language can the work begin.

At GoldSpot Discoveries, a start-up based in Toronto that is also focused on AI-powered target generation, this still means crafting a tailor-made exploration solution that closely hews to the conventional prospecting model.

That means gathering together much the same data as possible that they would rely on to make a conventional prediction, before cleaning it and then using its proprietary AI solutions – tailored to the metal type and location by trained geologists – to recognise patterns that indicate possible mineral locations. These findings are then confirmed by sampling expeditions in the field.

“You can try a whole variety of different algorithms or approaches, but that’s kind of just an appendix to the main operation, which is [thinking about] what do you do as a good geologist, and what can you do more robustly because you’re using AI and data analytics?” says GoldSpot’s chief technology officer, Shawn Hood.

Minerva, meanwhile, has adopted a different approach. Rather than gathering together all the necessary data and running it through machine-learning algorithms, Cantor and his colleagues have invested in an ontological approach, wherein all the data gathered on a claim area in the field is compared with an ecosystem of geological terms and rules pertinent to the kind of mineral or metal deposit they are trying to find.

This “cognitive AI system”, as Minerva terms it, has led to the creation of several dedicated applications, from its dedicated exploration platform Target, to document organisation programmes Leo and Solace, which spot geohazards.

The start-up argues that its approach is not only more generalisable than machine learning, since it doesn’t require massive amounts of training data – ideal for parts of the world where that is absent to begin with – but is also more transparent.

By using an ontological approach, users can trace back any decision made by the application along the path of rules governing the relationships between domain names. This is vital, Cantor says, in building trust in these types of AI solutions, the machine-learning and deep-learning variants of which are so often criticised as being effective “black boxes”, whose decision-making has almost to be unpicked.

Golden payload

Both approaches have yielded sizable pay dirt. In 2018, GoldSpot worked closely with Yamana Gold to extend the life of the latter’s El Peñón mine in Chile, helping to generate new deposit targets for the operator. As recently as September, meanwhile, the start-up pinpointed a 60m-long gold-hosting quartz vein in Elmer East, northern Quebec.

“It’s a totally data-driven AI discovery, and it was validated in the field using traditional prospecting techniques,” explains Hood, who argues that a conventional exploration effort would see only a tenth of the available data being analysed to generate new targets.

“Here, we had a holistic data integration involving many different kinds of geologists working together, setting the parameters of the algorithm, running it, getting results, and then going to look at those and, happily, finding a new showing.”

Minerva has been busy too. Last year, the technology start-up began working with the Yukon provincial government on an update of a mineral exploration programme originally commissioned in 2004. By running the original study through the start-up’s software, the new survey generated some 2,374 new targets using data collected from 22,144 sediment and stream samples.

Minerva has made its Terra Mining AI Suite available to operators in East Asia and Australia, and has even used its software to prospect entire countries. Thus far, interactive exploration maps have been generated for Papua New Guinea, Brazil and, most recently, Mexico.

“They were working with some local consultants who had been used to the amount of work that it normally takes for you to do that kind of analysis,” says Cantor. By using Minerva’s Target platform, the entire team was able to accomplish a task that would have normally taken most of the year in three months.

“It afforded them the ability to research the actual underlying regions a lot more, because they didn’t have to spend any of their time coming up with the initial first-pass targets.”

Mineral exploration technology going forward

For Cantor, these are but a few signs that the mining industry at large is beginning to embrace a central role for AI in exploration. Minerva’s head of geology sees opportunities for automation up and down the value chain in prospecting, from natural language processing to instantly standardised raw field data, and the mass digitisation of survey maps.

“Hopefully, the days of coming to a project and everyone’s just entering stuff into Excel sheets and trying to do their best” will fade away, says Cantor.

An attitudinal change is also at work, says Hood. Public understanding of the broader potential of AI is becoming more nuanced, he says, which is spilling into the mining industry.

“There’s now a saturation of the techniques, of ideas [about AI] across social media, conference short courses, conference presentations, technical literature,” he says. “And this is communicating these ideas to the masses in a way that are not just buzzwords, but actually have a bit of meat behind them.”

Most importantly, more and more AI-literate geologists are now entering the profession. “The landscape is now mature enough that it’s attracting the right people,” says Hood, who observes that most geologists working in mineral exploration now belong to a generation that grew up with the internet.

For them, AI is not a quasi-magical solution to their exploration woes, but will become just another tool to help them parse the mountains of data that constitute the modern prospecting process.

“They have the background of understanding that this is not weird computer voodoo,” says Hood. “They get it; they understand what’s happening. And they understand it well enough that they want to use it, and they want to use it themselves.”

This article first appeared in World Mining Frontiers magazine.