Local solar mini-grids could be the answer to the energy issues in rural Africa but won’t be feasible at scale without subsidies, a group of investors has claimed.

Managing about $2bn (£1.5bn) and roughly 100 completed or under-construction mini-grids in the area, the twelve energy and impact investors say the financial risks are currently too high to attract sufficient money for what they feel could fix one of the world’s biggest electricity access issues.

“The capital is there and waiting to invest, but there is a missing piece,” Reuters was told by Nico Tyabji, director of strategic partnerships with SunFunder, which offers debt financing for solar projects.

How public funding could help build a solar mini-grid network

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates the number of people in the world currently living without access to electricity is roughly 1.1 billion, significantly less than the 1.7 billion at the turn of the millennium.

A disproportionately large amount of this disadvantaged population lives in sub-Saharan Africa, however, and the intergovernmental organisation predicts about 600 million of the region’s 674 million residents will be without power by 2030.

It recently released a report which showed mini-grids offer the cheapest route to solving the issue and achieving universal electricity access by 2030, but also that there is not yet enough private investment for this to work.

Mr Tyabji and his fellow investors argue public money used to pay mini-grid developers and operators, based on the number of connections they make, is the potential solution.

He said: “Taxpayer funding has long-backed expansion of national power grid systems around the world, and the new subsidies would be in line with that.”

A closer look at rural Africa’s electricity access problem

Sub-Saharan Africa’s lack of electricity access is debilitating, causing various measurable detriments from severely limited healthcare infrastructure, lowered agricultural output and stymied technological innovation, to name but a few.

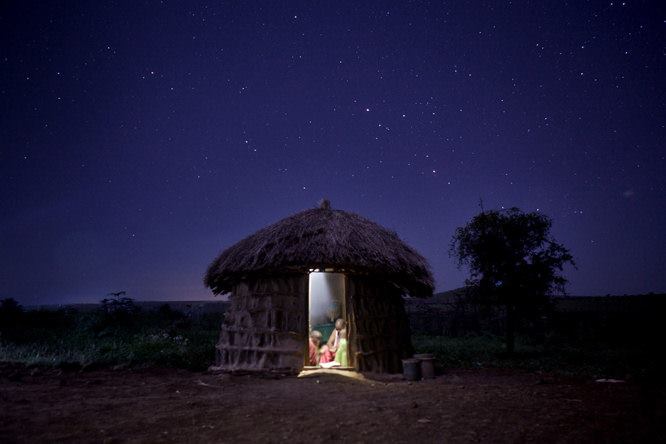

But things get markedly murkier when trying to assess, for example, the negative effect on a country’s future when its children can only study by candlelight after the sun has gone down.

Even Africans with access to the grid are perpetually hampered by disruption as a result of out-dated power generation, transmission and distribution technology, as well as an insufficient capacity for robust maintenance and repair.

In Nigeria, a country with a relatively high grid connection rate, a study by research network Afrobarometer found just 18% of people with access to electricity had it when needed, with the other 82% forced to rely on diesel or gasoline generators instead.

To make matters worse, Africa’s population is growing all the time: Out of the additional 2.4 billion people projected between 2015 and 2050, the UN predicts 1.3 billion will be born on the continent.

The need for electricity, it seems, is rising at a commensurate rate, as the IEA anticipates energy demand, which stood as high as 423 terawatt hours in 2010, will grow by 4% annually through to 2040, heightening the scale of the challenge with each passing year.

The Paris-based group suggests to meet the exponentially widening gap would mean doubling current levels of yearly investment in the continent, with almost all of the pot needed in sub-Saharan Africa.