A shortage of critical minerals is on the horizon that threatens to jeopardise the low-carbon transition and destabilise global energy security, unless immediate efforts are made to safeguard future supply chains.

Widespread electrification and the switch to renewable energy technologies will create unprecedented demand for products like lithium, copper, cobalt, nickel and rare earth elements, which are used to manufacture the batteries, turbines, solar panels and power cables that will underpin a decarbonised energy system.

But to keep pace with this expected demand surge for critical minerals, mining companies will need to rapidly expand their existing production capacity to avoid a supply shortage that would derail the energy transition and potentially trigger price swings in commodity markets.

Against this backdrop, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has urged policymakers to address the “looming mismatch” between supply and demand by sending clear signals to the market about their low-carbon intentions, “to ensure that critical minerals enable an accelerated transition to clean energy, rather than becoming a bottleneck”.

“This mismatch is something that worries us,” said IEA executive director Dr Fatih Birol, speaking to reporters. “Critical minerals are not a sideshow in our journey to reach climate goals – they are a part of the main event.”

He added: “Investors have not yet been convinced by governments’ pledges to reduce emissions. If they get unmistakable signals that clean energy technologies are the technologies of tomorrow, I believe investment will flow towards [mineral] deposits and we will see critical minerals production grow.”

In a report published today (5 May), the Paris-based energy watchdog emphasised this “crucial role” policymakers have to play in reducing the risks of investment for mineral producers.

“If companies do not have confidence in countries’ energy and climate policies, they are likely to make investment decisions based on much more conservative expectations,” it stated.

Energy-related demand for key metals and minerals could grow six-fold by 2040

According to the IEA report, titled The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions, a Paris-aligned effort to meet net-zero by mid-century could lead to a six-fold increase in overall mineral requirements for clean energy technologies by 2040.

At an individual commodity level, energy-related technologies could account for 40% of copper and rare earth element demand by 2040, 60-70% of demand for nickel and cobalt; and almost 90% of demand for lithium.

“Not only is this a massive increase in absolute terms, but as the costs of technologies fall, mineral inputs will account for an increasingly important part of the value of key components, making their overall costs more vulnerable to potential mineral price swings,” the IEA added.

The growth of electric vehicles – which the agency has said could number between 145-230 million globally by 2030 – along with battery storage, is expected to raise lithium demand more than 40 times by 2040, while demand for other battery ingredients including cobalt and nickel could increase 20-25 times over the same period.

Copper demand could more than double as countries expand their electricity networks and install more power lines, while for rare earth elements it could grow three to seven times higher compared to current levels.

These forecasts “raise huge questions about the availability and reliability of supply”, including market volatility that could push up the prices of these minerals and in turn delay the energy transition.

“Given the urgency of reducing emissions, this is a possibility that the world can ill afford,” the IEA warned.

Risks associated with critical minerals shortage will define 21st century energy security

Investment into new production capacity is clearly needed, but due to the long project lead times of mining operations – an average of 16 years, according to the agency – that investment needs to happen soon in order to respond to future demand trends.

“Long-term visibility is essential to provide the confidence investors need to commit to new projects,” said Dr Birol. “Efforts to scale up investment should go hand-in-hand with a broad strategy that encompasses technology innovation, recycling, supply chain resilience and sustainability standards.”

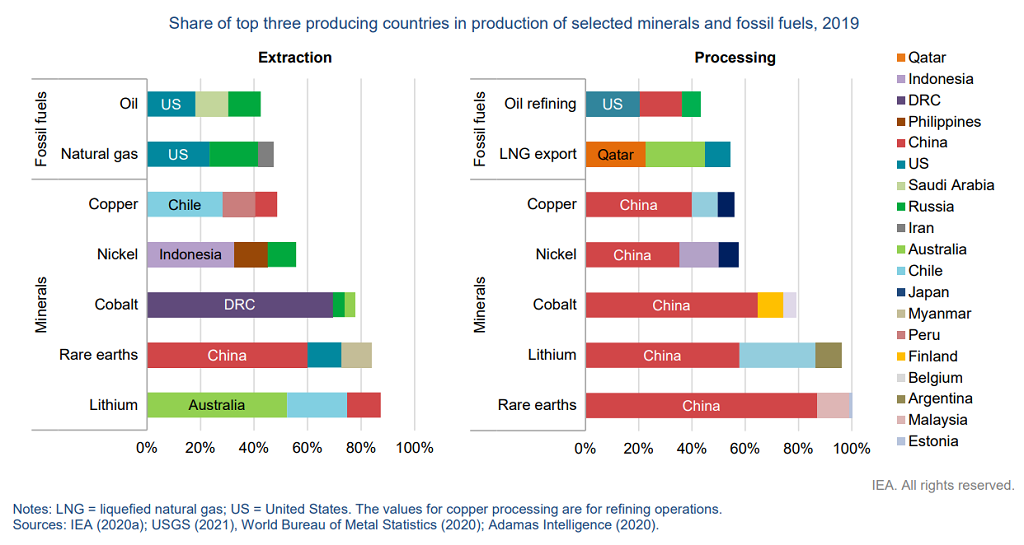

Additionally, the concentration of these mineral resources in a handful of countries – the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) holds almost half of the world’s cobalt reserves and accounts for around 70% of global production, for instance – poses potential supply chain vulnerabilities.

The world’s top three critical mineral producers – DRC, China and Australia – currently control well over three-quarters of global output, the IEA report shows.

In terms of mineral processing, this regional concentration is even more pronounced with China dominating across all sectors. The country’s share of refining is around 35% for nickel, 50-70% for lithium and cobalt, and nearly 90% for rare earth elements.

These factors, combined with complex and often opaque supply chains, present challenges that will need to be overcome as the energy transition gathers pace, with supply risks potentially arising from physical disruptions, trade restrictions and geopolitical developments as global demand for these commodities grows.

“This is what energy security looks like in the 21st century,” said Dr Birol. “These hazards are real, but they are surmountable. The response from policymakers and companies will determine whether critical minerals remain a vital enabler for clean energy transitions or become a bottleneck in the process.

“There is no shortage of resources worldwide, and there are sizeable opportunities for those who can produce minerals in a sustainable and responsible manner.”