The ‘Clean Energy For All Europeans package’, usually referred to as the ‘Winter Package’, presents the key remaining elements for full implementation of the EU’s 2030 climate and energy framework. Staff report

An ambitious Energy Union coupled with a forward looking climate change policy, via the implementation of the 2030 climate and energy framework and the follow-up to the Paris Agreement, was one of six priorities listed by the three presidents of the EU, Martin Schulz, (European Parliament), Robert Fico, (European Council), and Jean- Claude Juncker, (European Commission) when they signed, on 13 December, a Joint Declaration listing the EU’s legislative priorities for 2017. The Clean Energy For All Europeans package, published on 30 November 2016, was listed as a primary instrument of the Declaration.

It consists of numerous legislative Proposals together with accompanying documents, aimed at further completing the internal market for electricity, implementing the Energy Union and keeping the EU competitive as the widespread clean energy transition changes global energy markets.

But the Commission wants the EU to lead the clean energy transition, not merely adapt to it. For this reason the EU has committed to cutting CO2 emissions by at least 40% by 2030 while modernising the EU’s economy and delivering on jobs and growth for all European citizens. The updated proposals have three main goals: putting energy efficiency first, achieving global leadership in renewable energies and providing a fair deal for consumers.

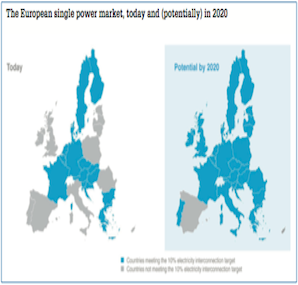

The Winter Package aims to promote these goals by establishing a common power market design across the Union and to ensure the adequacy of its power systems, to promote the better integration of renewable sources, to advance energy efficiency, energy cleanliness and energy performance to achieve the Union’s climate goals, and to implement rules on the governance of the Energy Union.

Consumer participation

Consumers across the EU will in the future ‘have a better choice of supply, access to reliable energy price comparison tools and the possibility to produce and sell their own electricity’ by virtue of increased transparency and better regulation. The package also contains measures aimed at protecting the most vulnerable consumers.

The Commission’s ‘Clean Energy for All’ proposals are designed to show that the clean energy transition is the growth sector of the future. Clean energies in 2015 attracted global investment of over €300 billion. The EU believes it is well placed to use its research, development and innovation policies to turn this transition into a concrete industrial opportunity. By mobilising up to 177 billion euros of public and private investment per year from 2021, it says this package can generate up to 1% increase in GDP over the next decade.

Investment

The EU has fixed its ambitions for climate and energy policies up to 2030 and the Commission is now putting forward the proposals necessary to meet them. The strengthened and expanded European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI 2.0) will focus even more on sustainable investments. In September 2016, the Commission proposed extending its duration until the end of 2020, thereby increasing the total investment target from €314 bn to at least €500 bn.

At least 40% of EFSI resources reserved for infrastructure and innovation will support operations in line with the Paris climate agreement objectives. An extra €177 billion is needed annually from 2021 to reach the EU’s 2030 climate and energy goals. Of the €154 billion investment triggered through EFSI so far, a quarter is energy sector related.

The intention is to use the successful EFSI model by adapting it to smart and efficient energy usage. A ‘Smart Finance for Smart Buildings’ initiative is proposed, to help finance renovation and retrofitting in the largely inefficient housing stock. There are opportunities for combining EFSI with structural funds, which represent €18 billion for energy efficiency during 2014-2020.

The starting propositions are that 20% of the EU budget should go to climate- related expenditure, and at least 40% of the infrastructure projects under EFSI should contribute to climate action. This should result in an investment of an extra €177 bn per year from 2021, to meet 2030 climate & energy targets, and contribute to economic growth with a 1% increase in GDP. The carbon intensity of the economy would be 43% lower in 2030 than in 2015, with 72% of power generation from non-fossil fuels.

Legislation

Among the legislative Proposals are:

- Recasts of the Internal Electricity Market Directive and its Regulation

- Repealing the Security of Supply Directive

- Recasting the Renewable Energy Directive

- A revised Energy Efficiency Directive;

- A revised Energy Performance of Buildings Directive

- A Regulation on the Governance of the Energy Union.

The new power market design is intended to better fit future electricity markets, which will be characterised by more variable and decentralised production, an increased interdependence between systems cross- border and opportunities for consumers to participate in the market through demand- side response, auto-production, smart metering and storage.

For the internal market the recast proposal (based on the existing Directive 2009/72/ EC), contains certain essential changes and modifications and the scope has been extended. Dates for its publication and entry into national law have not yet been set.

In terms of market organisation there is a further push for market-based (supply) pricing with possibility of public intervention for vulnerable consumers. There will be a reinforcement and expansion of rights of consumers, who will be entitled to enter into dynamic pricing contracts reflecting spot prices, and restricting termination fees, and enter into agreements with demand- response providers and aggregators without the supplier’s consent.

Role of TSOs

Transmission system operators’ existing provisions are largely maintained, with clarifications concerning energy storage, ancillary services and the new regional co- ordination centres.

They will be expected to co-ordinate with neighbouring TSOs and with the newly introduced regional operational centres, and perform tasks relating to the procurement of (balancing and non-frequency) ancillary services from market participants to ensure operational security in a way that is transparent, non-discriminatory and market- based, to ensure effective participation of all market participants; and develop a 10-year network development plan at least every 2 years (previously, every year).

Moreover, TSOs will not be allowed to own, manage or operate storage facilities, nor own or control assets providing ancillary services, unless certain conditions are fulfilled, including, among others that the ancillary services are non-frequency, and a lack of interest by other parties. The interest in storage of other market participants is to be reassessed at least every 5 years.

National regulation

In order to carry out their functions, NRAs will be granted additional powers to issue (joint) binding decisions on electricity undertakings and regional operational centres, carry out investigations and give instructions for dispute settlement, request information and impose penalties.

Market regulation

A recast Regulation, (based on the existing Regulation (EC) No 714/2009) aims at setting fundamental principles for well-functioning, integrated electricity markets, which allow non-discriminatory market access for all resource providers and electricity consumers. It would be binding and applicable in all Member States from 2020.

On balancing markets there will be rules, both for energy and capacity, including free access by all market participants individually or by aggregation. Market participants will be held financially responsible for imbalances they cause. In dispatch, demand-response must be non-discriminatory and market- based. Priority dispatch is allowed for small renewables or high-efficiency cogeneration installations with an installed capacity of less than 500 kW, and for demonstration projects for innovative technologies.

Congestion must be solved with non-transaction based methods (ie, not involving a selection among market participants). Capacity must be allocated through explicit or implicit auctioning, including both energy and capacity. TSOs will not be allowed to limit the volume of interconnection capacity to be allocated in order to solve congestion inside their own control area or as a means of managing flows on a border.

Distribution tariffs must reflect the cost of use of the distribution system by system users, including so-called “active consumers”.

Member States may introduce capacity mechanisms, provided they are justified by a resource adequacy concern documented in a European resource adequacy assessment.

Organisation for DSOs

It is proposed to introduce a European entity for DSOs as a platform for co- operation among DSOs that are not part of a vertically integrated undertaking or that are unbundled, to promote the completion and functioning of the internal market. The tasks of the new entity will include, amongst others, planning of transmission and distribution systems, integration of renewables, development of demand-side response, digitalisation of distribution networks and co-operation with ENTSO-E.

Capacity mechanisms

The Commission’s Final Report outlining the conclusions of the Commissions Sector inquiry into capacity mechanisms in the light of state aid constraints has been published.

In the Commission’s view, the ideal capacity mechanism should be open to all potential domestic and foreign capacity providers, with specific attention to new entries, feature a competitive price- setting process that ensures a competition on prices to minimise the price paid for capacity, ensure incentives for reliability and investment in interconnection; and be designed to co-exist with scarcity pricing to avoid overcapacity and trade distortions.

Renewable energy

The Proposal for a re-cast Directive on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources is based on the existing Directive 2009/28/EC. The recast Directive aims at tackling the existing issues hampering renewable energy deployment, such as investor uncertainty, administrative hurdles, the need to improve cost- effectiveness of renewables deployment and the need to update the policy framework. It would come into force on 1 January 2021.

Key features are an EU-wide minimum target of 27% share of renewables in gross final consumption by 2030, with Member States obliged to reach a minimum national share of between 10% and 49%.

The contribution of biofuels consumed in transport, if produced from food or feed crops, would be limited to 7% of the final consumption of energy for road and rail in that Member State by 2020, further reduced to 3.8% by 2030. At the same time, the share of biofuels and biogas produced from certain feedstock used in the transport sector is supposed to gradually increase. The proposal also requires that support mechanisms should be granted in an open, transparent, competitive, non-discriminatory and cost- effective manner.

A new provision on the stability of financial support ensures that the level of, and conditions attached to, the support of renewable energy projects are not altered in a way that negatively impacts the rights or the economics of supported projects.

Critically, the rules on priority grid access for renewables have been removed, and there is a whole new set of rules designed to streamline and speed up permitting.

Energy efficiency

The EU regards energy efficiency as a primary source for climate control purposes and proposes a revision of the existing Directive on Energy Efficiency 2012/27/EU.

The revised Directive amends existing Articles that are directly related to achieving the 2030 targets and introduces a few new Articles to extend consumer rights and increased access to smart metering tools, billing and consumption information. The new directive would confirm a 30% binding energy efficiency target for 2030, but does not impose national binding targets on Member States.

Next steps

The Winter Package’s legislative proposals will go through the Ordinary Legislative Procedure before becoming binding Union legislation, so the European Parliament and the Council need to agree on a common text and adopt the Proposals. The average length of the Ordinary Legislative Procedure is around 18 months.