Charles Hendry, a former energy minister, was appointed by the UK government in May 2016 to carry out an assessment of the role tidal lagoons could play in the UK’s energy mix. In January his generally favourable report, ‘The role of tidal lagoons’, was published. By Leonard Sanford

At 183 pages this is a long report to have been produced in six months, but its central purpose and conclusion has been more briefly expressed by its author in the report’s introduction: “This is not … just about how we decarbonise the power sector in the most cost effective way now; it is also about very long-term, cheap indigenous power, the creation of an industry and the economic regeneration that it can bring in its wake. After years of debating, the evidence is I believe clear that tidal lagoons can play a cost-effective part of the UK’s energy mix. Large scale tidal lagoons, delivered with the advantages created by a pathfinder, are likely to be able to play a valuable and cost competitive role in the electricity system of the future.”

The aim of the review was to determine whether tidal lagoons could play a cost effective role as part of the UK energy mix, the scale of opportunity in the UK including supply chain opportunities, a range of possible structures for financing tidal lagoons, the suitable project size for a ‘pathfinder’, and whether a competitive framework could be put in place for the delivery of tidal lagoon projects. But it was not an assessment of competing technologies.

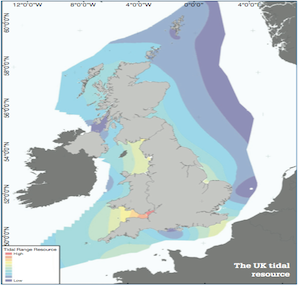

The UK government’s response to the report was to acknowledge that such a complex issue would require time for the assessment of its recommendations, but that such an assessment would be published in due course, perhaps by late March. Possibly it will be mindful of the now-disbanded Department of Energy & Climate Change’s estimate that theoretical tidal power capacity in the UK could range up to 30 GW.

Proposals for tidal lagoon projects such as Swansea Bay have been put forward for many years but development and funding support from governments have not been made available. Recently any potential support has been subject to delays while the government establishes its position on what subsidies will be available going forward. It remains to be seen whether this positive review will turn the tide for projects such as Swansea Bay or whether further delays will continue to push out deployment timescales.

Dissent

The reception of these recommendations by industry has been broadly positive, and keen for the government to take steps to place the UK at the global forefront of tidal power. However, some commentators have questioned the subsidy cost and strike price estimates set out in the review, claiming that they are overly optimistic and stating that the £1.3bn Swansea Bay project remains too expensive.

Economic range

It is encouraging for tidal power that the UK has some of the largest tidal ranges in the world, including the second largest, which is found in the Bristol Channel. The report made a number of recommendations and observations for tidal lagoon projects. Crucially, it concluded that a UK tidal lagoon programme has the potential to be valuable and competitive in comparison with other low carbon energy projects.

Based on subsidy cost forecasts, the review estimates that the average additional cost passed on to a household’s annual electricity bill by a smaller-scale pathfinder tidal lagoon project (such as that currently proposed at Swansea Bay) would average 35 to 45p during the first fifteen years, reducing to 20 to 30p for 30 to 60 years. For larger scale projects, this figure would be £1.85 to £2.10 in the initial stages, reducing to 50p to £1.40 thereafter. If this analysis is accurate tidal lagoons will be more cost-competitive in the longer-term than either offshore wind or nuclear power, based on current projections.

Pathfinder project

The report considers that moving ahead with a small-scale (less than 500 MW) pathfinder project is a “no-regrets” policy, and suggests that there is a very strong case for doing so as soon as possible. The report stresses that a pathfinder would help establish tidal power technology and provide benefits from a gearing up of the UK supply chain as well as learning and efficiency gains.

Hendry’s view is emphatic. “The costs of a pathfinder project would be about 30p [£0.30] per household per year over the first 30 years. A large scale project would be less than 50p over the first 60 years. The benefits of that investment could be huge, especially in South Wales, but also in many other parts of the country. Having looked at all the evidence, spoken to many of the key players, on both sides of this debate, it is my view that we should seize the opportunity to move this technology forward now.”

The review recognises that the proposed 320 MW Swansea Bay tidal lagoon, which obtained development consent in 2015, is the only project currently well enough developed to fill this pathfinder role in the near future and leans heavily for some of its general conclusions on analyses of the project supplied by its developer. It urges the government to move swiftly to final-stage negotiations with the developer, Tidal Lagoon Power.

Financing

A contract for difference (CfD) model is suggested as the most appropriate form of government support for a pathfinder project. Under a CfD model the government would contract with the developer to set the price received by the project for electricity generated during the contract term (known as the ‘strike price’), with payments likely to be funded in part via levies on consumers’ electricity bills. The review suggests that a CfD term of no more than 60 years would be appropriate, in contrast to the 90 years being sought by Tidal Lagoon Power. However, an alternative regulatory model should not be ruled out as an option to support a longer term programme. The review includes extensive analysis of how strike prices for tidal lagoon projects could be formulated and how related costs can be meaningfully compared with other low carbon technologies. The review’s general conclusion is that large-scale tidal lagoons have the potential to be competitive with those technologies by the mid to late-2020s.

Hendry also concludes that competition for government support for tidal lagoon projects (such as through CfD and associated contracts) should be by a site-specific competitive tendering process rather than by auction.

National policy

Hendry considers that a central level of co-ordination for a national tidal lagoon strategy would help maximise gains, and proposes that the consenting process for large-scale tidal projects should therefore be informed by a National Policy Statement (NPS), under which the government designates specific sites as suitable for development. But to avoid delays to the proposed Swansea Bay tidal lagoon, the review suggests that this pathfinder should be excluded from the NPS approach.

Tidal power authority

The review recommends the establishment of an ‘arms-length’ Tidal Power Authority, accountable for maximising UK advantage from the tidal lagoon programme and ensuring value for money. This body would not have any planning or consenting powers but would be responsible for deciding which locations should be offered to tender and when, for carrying out initial environmental assessments for specific locations, for fostering new industry and driving cost reductions; and advising the government – including in the development of the NPS.

Future programme

The pathfinder should be commissioned, and be operational for a reasonable period before financial close is reached on the first larger- scale project. The pause would allow in-depth monitoring to be carried out and assessed, and research to be conducted, to address issues as they arise.

The report suggests that if the UK is to adopt tidal technologies, and tidal lagoons in particular, and to obtain the industrial benefits of such an approach, then it needs a strategy similar to that for offshore wind, with a clear sense of purpose and mission. It needs to bring the industry together to address each challenge as it emerges and to set the industry itself the goal of making the step-changes which would determine whether this becomes a new industry, or a small ‘niche’ enterprise.